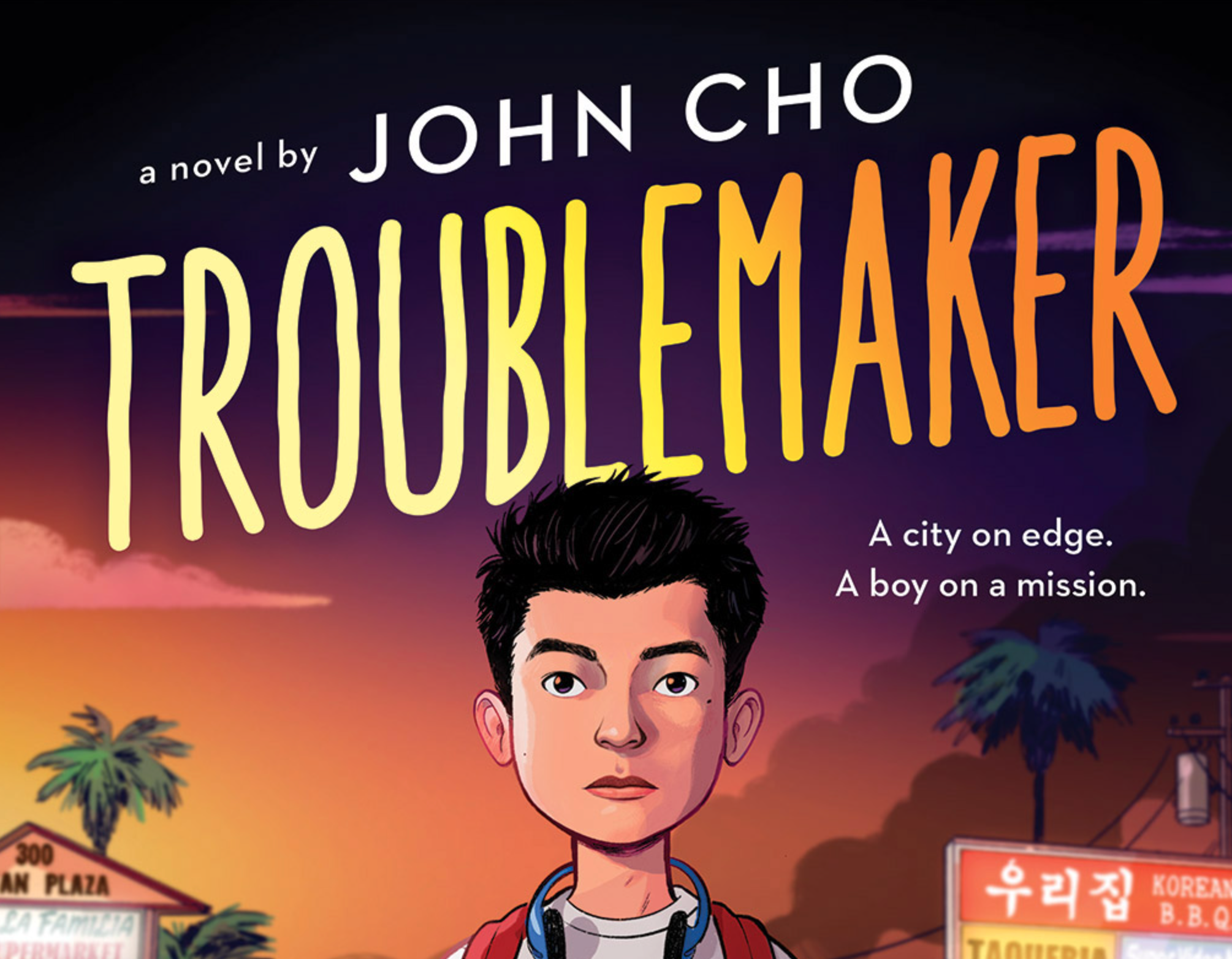

It’s at this inflection point that Korean American actor John Cho has set his first novel, Troublemaker, a galvanizing middle-grade offering that follows the L.A. riots through the eyes of 12-year-old Korean American Jordan Park, whose parents own a liquor store. When Jordan’s father leaves to check on the store amid mounting unrest, Jordan and his friends set out on a perilous journey to help his dad, and Jordan is forced to face the racism plaguing his own community.

Excerpt from Troublemaker, by John Cho

CHAPTER ONE

Apr 29, 1992

I never knew a pair of shoes could scare me so much, but when I see Umma and Appa’s sneakers by the door when I walk in, I nearly jump right out of my skin. It’s not that they’re anything out of the ordinary. The shoes, I mean, with Appa’s laces fraying at the ends and Umma’s looking more gray than white like they did when she first bought them. What’s weird is the fact that they’re here at all. It’s just a little after 4 PM on a Wednesday and Umma and Appa should both be at the store. Not at home.

I thought I’d have more time before I’d have to face them today.

Their voices are quiet, muffled, coming from the direction of the kitchen. I stand real still by the door, listening, but I can’t hear what they’re saying from here. I move carefully down the hall, gripping the straps of my backpack with both hands, praying in my head. Don’t see me. Don’t see me.

Just as I’m about to pass the kitchen, Umma looks right up at me.

“Oh Jordan, you’re home?” she says in Korean. She says it all casual like she’s here every day when I get home from school, like I’m not the one who should be saying, “Oh Umma, you’re home?”

“Yeah,” I say back in English. A nervous feeling starts to spread through my stomach. My prayer changes. Don’t ask me how school was. Don’t make me lie to you.

By some miracle, she doesn’t. She just smiles and nods, turning back to Appa to carry on talking about whatever they were talking about, the air kind of tense and tight between them.

Huh. That’s weird. Umma always asks how school was. It’s pretty much her favorite question. Not to mention, I still don’t know what they’re both doing home so early. I linger by the door, wondering whether I should ask or not. But the more questions I ask them, the more questions they might ask me. And I want to avoid that for as long as possible.

Not that Appa would ask me anything though. This whole time, he hasn’t even looked at me once. I don’t know whether to be relieved or disappointed.

It’s been this way between us for weeks, ever since our Big Fight. Things haven’t been the same since then. It’s like time split into a Before and After. Before: when I was just Jordan and he was just Appa, and I didn’t think twice about being in the same room together. After: when we’re not just Jordan and Appa anymore. We’re Jordan Who Doesn’t Know What to Say Around Appa, and Appa Who Basically Completely Ignores Jordan. He’s been so cold to me lately. Colder than a brain freeze.

Maybe he’s waiting for me to say sorry first, but there’s no way I’m going to do that.

Maybe this means we’ll never talk again until the end of time. Maybe not even then.

I stare at the back of his head for a second longer and then I walk away.

Harabeoji’s in the living room, watching TV and eating ojingeo off a plate. At least grandparents are dependable. Always where you think they’ll be, sitting on the couch wearing a fishing vest with a hundred pockets even though you can’t remember the last time you’ve ever actually seen them go fishing, a piece of dried squid between their teeth. At least, that’s my grandpa. I don’t really know about anyone else’s grandparents.

“Hi Harabeoji, I’m home,” I say, dropping my backpack on the floor and sitting down next to it.